When is the best time of year to visit Japan?

If you have always dreamed of touring the timeless temples of Kyoto, sampling the scrumptious street food of Osaka, meandering through the monumental mountains of Nagano, or diving with dolphins and hammerhead sharks in Okinawa, the best time to visit Japan is now! Following two years of strict border restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Japan reopened its doors to international tourists in the latter half of 2022, welcome news to those who had long imagined a trip to the Land of the Rising Sun and those who just couldn’t wait to get back. Still, whether first-time visitor or repeat traveler, you might be wondering: when is the best time of year to visit Japan? Read on!

Before I first moved to Japan in 2008, I had never once given a thought to the country’s climate. Back then, Japan existed in my mind solely as a series of still photographs: temples, packed trains, skyscrapers, Mt. Fuji. I never paid much attention to whether the people in those photographs were wearing jackets or short sleeves. Or mopping their sweaty brows with wet handkerchiefs.

That same climate dealt me a swift damp slap of reality from the moment I landed at Narita Airport with my clothes in a backpack and my bicycle in a cardboard box. It was the first week of August, a time of year in Japan when temperatures soar into the 30s and the humidity, more significantly, creeps above 80%.

Having lived previously only in western Canada and southern England, I had never experienced anything like it. With no air conditioning in my new apartment for the first two weeks, I spent a considerable amount of time in the bathtub, filling it to the brim with cold water each night after work, and carried two extra T-shirts with me wherever I went.

The climate of Japan varies immensely not only by time of year but according to the country’s extreme variations in latitude and topography. While the icy northern tip of Hokkaido stretches above the 45th parallel (on a clear day, you can see Russia from your house!), the semi-tropical sands of the Yaeyama Islands are closer to Taiwan than the Japanese home islands. The southwest of Honshu (Okayama, Hiroshima and Yamaguchi) is known as the San’yo Coast (山陽, “sunny side of the mountains”), while a quick trip over to the Sea of Japan side will find you on the ruggedly beautiful, if slightly less hospitable, San’in Coast (山陰, “in the shadow of the mountains”).

Sample of Average Seasonal Temperature Ranges Around Japan

| Spring (Apr-June) | Summer (July-Sept) | Autumn (Oct-Dec) | Winter (Jan-Mar) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tokyo (Honshu) |

10°C-25°C | 26°C-36°C | 5°C-23°C | 0°C-14°C |

| Fukuoka (Kyushu) |

11°C-27°C | 22°C-33°C | 6°C-24°C | 4°C-15°C |

| Sapporo (Hokkaido) |

3°C-22°C | 19°C-26°C | -4°C-16°C | -7°C-0°C |

| Naha (Okinawa) |

18°C-30°C | 25°C-33°C | 16°C-28°C | 18°C-30°C |

And so it pays to keep all of this in mind when considering what might be the best time of year to visit Japan for you. Where do you want to go? What do you want to do? And how can you be best prepared, not just for the weather, but also for the best travel experiences that each time of year in Japan has to offer?

The Land of Four Seasons (四季)

One of the most common assertions you are likely to hear in Japan from locals (particularly those over a certain age…) is that Japan is not just a land of four seasons, but the land of four seasons (四季, shiki). If you are lucky, you may even get a list of the vaunted four: haru (春, spring), natsu (夏, summer), aki (秋, fall/autumn), fuyu (冬, winter). I used to try to explain that we too in Canada (and no doubt, many other countries around the world as well) experience much the same four, but this tended to meet with so much disbelief, confusion and rage that I soon tossed in the towel on that one.

I will concede, however, that the four seasons across much of Japan are remarkably distinct and swift in transition. The cold winds and clouds of February seem to shift in a matter of days to the blossoms and sunny skies of March. And a single typhoon in late September is often enough to blow off the steamy summer heat, heralding in the crisp cool air of autumn.

A Quick Guide to the Four Seasons in Japan - What to Wear, What to Eat, What to Do

Spring (March-May)

| What to Wear* | What to Do | What to Eat |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Summer (June-September)

| What to Wear* | What to Do | What to Eat |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Autumn/Fall (September-December)

| What to Wear* | What to Do | What to Eat |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Winter (December-February)

| What to Wear* | What to Do | What to Eat |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

*This is general advice based on weather in the major cities of mainland Japan (obviously if you are skiing in Hokkaido or lounging on the beach in Okinawa, your choice of apparel will differ!).

Nevertheless, regardless of actual meteorological reality, this concept of the four seasons is a powerful cultural idea in Japan, inextricably linked with literature (particularly poetry), music, fashion, travel, festivals, popular activities, and (especially) food. This is reflected heavily in advertising brochures or commercials for domestic tourists which frequently contain photographs of popular locations across the famed four seasons.

In the spirit of this tradition, this article takes you, prospective traveler to Japan, through each of Japan’s four seasons to help you make an informed decision about when to go and how to get the most out of your trip. Please note that I have listed the seasons not in chronological order in this article, but in general order of popularity among international tourists traveling to Japan:

When one encounters a friendly face in Japan, it is probably more common to comment on the weather than to actually say hello. Now, remarking on the beauty of a particular sunset or starry sky might be okay now and then, but people in Japan (much like people in the UK) understand that complaining about the weather is a far better way to forge the bonds of friendship.

Here are a few friendly complaints about the weather in Japanese to get you started:

- Kyō, atsui desu ne! - It’s hot today!

- Kyō, samui desu ne! - It’s freezing today!

- Kyō, kaze ga tsuyoi desu ne! - It’s windy today!

- Kyō, kafun ga sugoi desu ne! - There’s so much pollen* in the air today!

Spring (春)

行く春や Spring drifts swiftly by,

鳥啼き魚の Birds cry, and the eyes of the

目は涙 fish are filled with tears

Matsuo Basho (芭蕉松尾), 1644-1694

Spring is the most iconic time of year in Japan, and by far the most popular with both domestic and international tourists. Television stations and national newspapers track the progress of Japan’s renowned sakura (桜) cherry trees as they burst into bloom across the nation.

For hundreds of years, friends, family, and lovers have gathered under these pillowy pink clouds of delicate blossoms to toast the coming of spring. In Japanese art museums one can find hundreds of beautiful ukiyo-e paintings depicting lords and ladies cavorting under the sakura in the storied days of Edo.

Spring (April) also marks the beginning of the Japanese school year, meaning that the “back to school” image of Japan is one of pink blossoms fluttering to the ground rather than the autumn leaves of many other countries. This means that the sakura feature prominently in films, pop songs, and novels in Japan as symbols of the ephemeral realm of youth.

Spring is not, however, as consistent in terms of weather as the autumn. The season tends to be windy, with temperatures rising and falling unpredictably through March and even into April, so you should always come prepared for chilly winds and intermittent rain.

What to Wear

If you are visiting Japan in spring, be sure to pack the following in your suitcase:

- Long-sleeve shirts

- Light sweater or fleece

- Light rain jacket

- Trousers/jeans

- Sturdy walking shoes

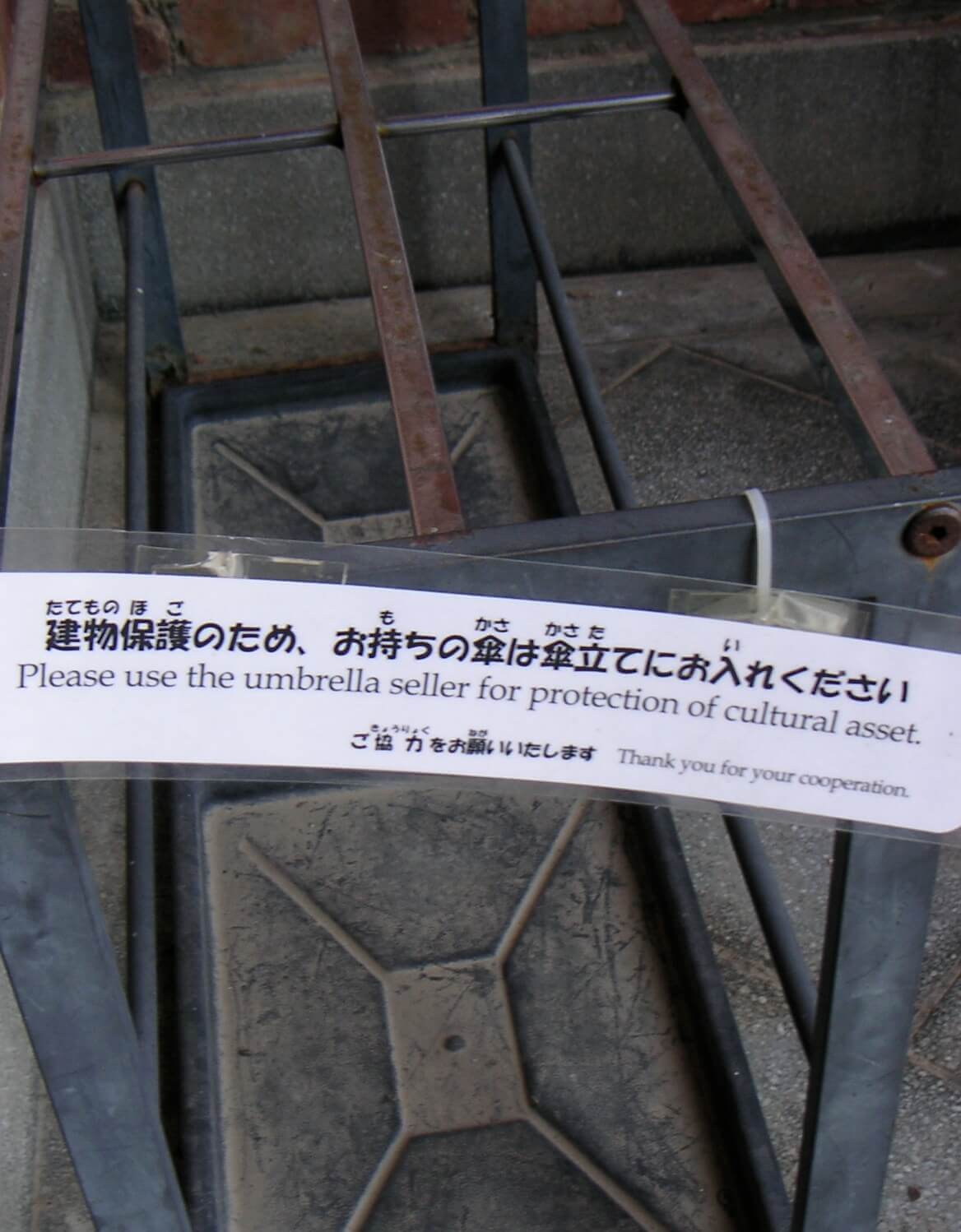

People in Japan generally carry umbrellas if there is rain in the forecast. Many women also carry higasa (parasols) in sunny or hot weather (quite a surprise to many first-time visitors!). However, the often blustery conditions in spring can make a good rain jacket (and waterproof trousers/shoes) a more practical and versatile option for travelers, particularly out in the countryside. If you decide you do want an umbrella, they are sold everywhere in Japan (even convenience stores) and are relatively cheap.

What to Do

Spring in Japan is all about getting out of doors to enjoy the country as its parks, forests and gardens burst into bloom. Those travelers more inclined to city life will find plenty of pleasant walks and quiet picnic spots just around the corner from busy train stations, while adventurous souls can hop on a bicycle or lace up some hiking boots to explore Japan’s beautiful countryside and stunning national parks.

Here are just a few ways to while away your time in Japan in spring:

O-hanami (enjoying the cherry blossoms)

O-hanami (お花見) is often translated into English as “cherry blossom viewing” but this makes it seem far more staid and formal than it actually is. While o-hanami is one of Japan’s proudest and most time-honored traditions (as depicted in paintings and etchings going back hundreds of years), the whole point of the thing is really just to gather under Japan’s spectacular sakura trees to drink and eat with family and friends.

O-hanami can also be whatever you want it to be, from a romantic lunch for two on Kyoto’s Arashiyama to a short family hike up Mt. Takao to a raucous boozy afternoon in Tokyo’s Yoyogi Park.

Normal o-hanami practice is to bring along drinks and snacks to share. Japanese people generally make use of plastic picnic sheets (removing their shoes first, of course) but these are not compulsory. Whatever you do, be sure to take your trash with you when you leave!

Cherry blossoms can be rather fickle flowers, blooming between mid-March and mid-April. They are also famously short-lived, their delicate blossoms gracing the branches of sakura trees for only a few days before fluttering beautifully to the ground.

Popular cherry blossom spots such as Kyoto, Yoshino, or Tokyo’s Meguro River can be extremely busy in the spring, with accommodation filling up fast and prices rising higher than normal. If you are not a fan of big crowds, keep in mind that while Japan’s cherry blossoms are very beautiful, a kaleidoscope of other gorgeous flowers (azaleas, phlox, tulips, wisteria...) continue to bloom throughout the spring season, making May and early June great times to visit the country as well. However, it is best to avoid Golden Week (a week of holidays in Japan running from the last days of April into the first few days of May), when seats on the shinkansen bullet trains sell out, hotels fill up, and freeways resemble parking lots. Pick another week!

If you’ve just got to see those cherry blossoms (and they are gorgeous), traveling across a few different regions of the country might help, as sakura bloom at different times in different places (Japanese TV tracks this daily with great accuracy and fervor). If you miss them in Fukuoka or Nara or Tokyo, you might get lucky in Hirosaki or Kanazawa.

Visit gardens, parks, shrines, and temples

Any month of the year is a good time for a visit to Japan’s thousands of traditional gardens, shrines and temples, but the colors of spring provide particularly vivid backdrops for the photographs of Japan that you have always dreamed of.

Beyond the sakura blossoms, many other spectacular flowers bloom throughout the spring in Japan, and the woods and rice-fields shed their winter dun and shimmer into green once more.

Aside from traditional spots, Japan also has many wonderful parks for families. Tokyo’s Shinjuku-Gyoen is a particularly gorgeous spot, as is seaside Kasai-Rinkai Koen (next to Tokyo Disneyland).

The contrast of the modern and the traditional is one of Japan’s most striking features, particularly in the capital city. Alongside the Tokyo Dome (home to the storied Yomiuri Giants baseball franchise) and its accompanying rollercoaster, you will find the picturesque grounds of the Edo period Korakuen Garden. The grandeur of the Meiji Shrine stands a block away from the wild fashions and bustling cafes of Harajuku. Austere Zōjōji Temple makes a compelling companion to the orange girders of Tokyo Tower. And futuristic Shinbashi is just a stone’s throw from the waterfront grounds of Hama Rikkyu Teien, where the Tokugawa shōgun and his friends used to shoot ducks!

Cycling/hiking

For some reason, tourism in Japan is not often associated with more active pursuits such as hiking and cycling, but opportunities for exploring the great outdoors on two wheels or two feet abound!

Spring is a great time to hit the trails for a hike. Beginners or those with limited time can opt for some of the gentler routes closer to the cities, such as Mount Tsukuba in Ibaraki or Mount Rokko in Kobe. Nokogiri-yama in Chiba, while more challenging, is a quick day trip from Tokyo and is a truly unique natural and historical site.

As for cyclists, while the bigger cities can be somewhat overwhelming at first, many of their rivers (such as Tokyo’s Arakawa and Tamagawa or Kyoto’s Kamogawa) have pleasant riverside cycle paths. Rental options in Japan have also recently improved, with decent bicycles available in certain locations such as Japan’s largest lake, Lake Biwa, as well as both ends of the Shimanami-Kaido (しまなみ海道), a spectacular bicycle route that traverses multiple islands on its way across Japan’s Inland Sea.

For more adventurous types, the hiking and cycling options are endless, but be sure to check weather conditions as snow can persist quite late into spring in northern and mountainous parts of Japan.

What to Eat

- Bento boxes - buy an appetizing bento at a local supermarket and enjoy it under the sakura.

- Sakura mochi - most traditional of the many sakura-themed sweets, these pink gelatinous rice-cakes can only be found in spring.

- Hatsugatsuo (the first bonito of the year) - generally seared on the outside and raw on the inside, this delicious fish is a highly prized seasonal delicacy.

- Cherries, melons

I’d recommend The Housekeeper and the Professor (博士の愛した数式) by Yoko Ogawa, a touching novel of friendship between an aging mathematics professor who is losing his memory and his young housekeeper and her son. The Twilight Samurai (たそがれ清兵衛, 2002), an Oscar-nominated film about an impoverished and widowed samurai retainer trying to take care of his family as the time of the samurai dwindles into its own twilight, is one of my all-time favorite Japanese films.

Autumn/Fall (秋)

この秋は The autumn passes,

何で年寄る And still I grow older–why?

雲に鳥 Birds among the clouds

Matsuo Basho (芭蕉松尾), 1644-1694

With blue skies, mild temperatures, and spectacular foliage, autumn just might be the best (and most underrated) time of year to visit Japan.

The hot humid weather of late summer normally dissipates in mid- to late-September, often quite precipitously after a late-season typhoon sweeps over the archipelago. Across much of Japan, the temperature remains pleasantly cool until mid-December, when it drops off into the true chills of winter. Rain falls occasionally, though less so as autumn progresses.

The main highlight for domestic Japanese tourists during autumn is definitely kōyō (紅葉), which literally means “red leaves” but in practice is composed of a breathtaking palette of orange, yellow, and scarlet red. While those accustomed to such seasonal changes in their own countries may shrug (as I, coming from Canada, once did), it must be said that the autumn colors of Japan are particularly dense, varied, and vivid.

It is also an especially great time to get out and explore the great Japanese outdoors, either on foot or two wheels. For those who prefer to sit back, relax, and let the scenery roll by, there are countless train and bus routes that traverse all manner of stunning natural terrain.

What to Wear

If you are visiting Japan in autumn, be sure to pack the following in your suitcase:

- Long-sleeve shirts

- Light sweater or fleece

- Light rain jacket

- Trousers/jeans

- Light gloves (later in the season)

- Walking shoes

Bringing layers is a good plan in autumn, as the evenings get a bit chilly, especially in the evenings. On the other hand, there are some days that are surprisingly warm (I normally wear shorts through November, which causes considerable surprise in Japan). Those traveling to the north of the country or the mountains will of course need to bring warmer clothing (from October onward).

What to Do

Similar to spring (and even more so, perhaps), autumn in Japan is a great time to get outside and enjoy the parks, mountains, rivers, and forests of Japan. From mid-October onward, travelers will be rewarded with spectacular landscapes of autumn leaves along with some of the best and most consistent weather that the country has to offer. The chill of evening also makes autumn in Japan the perfect time to gather around a warm meal with friends, relax in an onsen, or snuggle up with a book on your futon in a ryokan.

Here are just a few ways to while away the time in Japan in autumn:

Kōyō (autumn leaves)

Just as the emphasis for many Japanese tourists in spring is to snap just the right photograph of a sakura tree in mankai (full bloom), the cameras of autumn emerge to hunt down that one perfect Japanese maple in full blazing red (紅葉, kōyō).

The yearly changing of the leaves transforms Japan in autumn into a massive landscape painting of orange, scarlet red, and yellow brushed between stretches of evergreen. Hikers and cyclists who can access more remote areas will be rewarded with particularly outstanding views, but there are also plenty of simple city walks for those who prefer to take it easy, as well as train trips and bus tours that take in the majesty of the season.

Nikkō, home to the atmospheric Toshogu Shrine where shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu is enshrined as well as Nikkō National Park, is a popular kōyō destination just a short train trip from Tokyo. The Fuji Five Lakes are also particularly beautiful, with the lakes and their famous mountain forming the perfect backdrop to the autumn colors. If you come early in the season (mid-September to mid-October) and want to avoid the crowds, Daisetsuzan in Hokkaido is generally one of the first places in the country to see the leaves change.

Onsen (hot springs)

Japan’s volatile volcanic topography has brought the country one incredible blessing: thousands and thousands of hot springs (温泉, onsen) that bubble up right out of the ground. Soaking one’s body in these warm (or often, quite hot!) pools of water is a time-honored Japanese tradition that will soon melt your cares (and aches and pains) away.

Sitting in an onsen surrounded by trees full of autumn leaves is a particularly serene experience, so it is best to seek out a location that offers outdoor rotenburo (露天風呂).

The many onsen hotels of Hakone are an easy trip from Tokyo, as are those near Nikkō. Nyūtō Onsen in Akita is housed in traditional buildings frequently used for filming historical dramas. Those in search of something truly unique could opt for Hotel Iya Onsen on the island of Shikoku in the remote Iya Valley, which uses a funicular cable car to help guests access its riverside rotenburo!

Note that many onsen hotels or ryokan also offer “day bathing” (hi-gaeri onsen) where you pay a nominal fee to use the facilities without staying overnight. There are also some free onsen in very remote areas (though facilities are usually quite limited).

While the pleasure of soaking in a hot bath will undoubtedly appeal to many of you, it is important to be aware that visiting a Japanese onsen brings with it certain rules based on cultural norms.

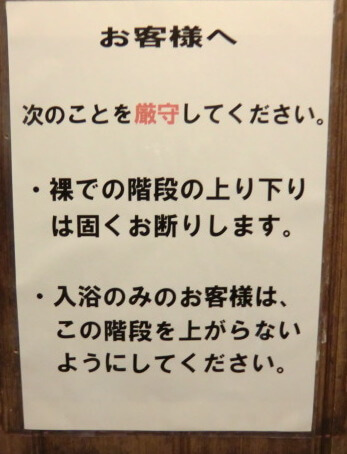

You must be naked. No trunks, no bikini, not even a Speedo. Starkers. Baths are (almost always, these days) segregated by gender. If this is a problem for you – culturally, religiously, or personally – you might want to avoid a trip to an onsen.

Tattoos are generally not allowed. If you can cover them, it might be okay. Otherwise, they are a no-go in most onsen in Japan.

Translation (sign, at right): "Ascending or descending the stairs naked is strictly prohibited."

Cycling and Hiking

With drier weather (usually) and more consistent temperatures, autumn is a great time to go hiking or cycling in Japan.

Adventurous types might want to head somewhere like the forests and hills between Fukushima and Niigata for exciting hiking or cycling. If you’d prefer a more leisurely stroll or pedal through the leaves, head to the Fuji Five Lakes (bicycles rentals available) or one of the major parks in Tokyo or Kyoto.

Take a scenic train trip

Japan’s trains are known for comfort and efficiency, but the country can also lay claim to some of the world’s most glorious train rides.

The “Hakone day circuit” is a favorite day trip for train enthusiasts, beginning with a special climbing train that travels up a series of switchbacks and finishing (no joke) with an actual pirate ship across the lake. The autumn leaves will literally smack against your train windows.

You could also take the Eizan Line train from Kyoto up to the small villages of Kibune and Kurama, a stretch of which is lined on both sides by Japanese maple trees, known as the Momiji Leaf Tunnel. If you are traveling with children, you can ride behind an actual Thomas the Tank Engine (or a steam locomotive from the 1930s) along the Oigawa Railway in Shizuoka.

What to Eat

- Grilled sanma (saury) - Japan is home to so many (so many) delicious fish that are completely unknown elsewhere. The first time I ate sanma, all I could find on English Wikipedia was that it was “a fish eaten in Japan.” The fish, a cultural reference point for autumn in Japan, is best enjoyed grilled.

- Kuri (chestnuts) - roasted chestnuts are a favorite autumn snack and also feature in a wide variety of sweets and seasonal dishes.

- Yaki-imo (roasted sweet potato) - if you are lucky, you may hear the call of the yaki-imo truck making its rounds (think “ice cream van” but with a fiery oven full of potatoes in the back). Once common, these trucks are now something of a rarity, as yaki-imo can now be bought more easily and cheaply at supermarkets and convenience stores. Most kids in Japan love nothing more than to rip open a piping hot yaki-imo and dig in.

- Kaki (persimmons), mikan (mandarin oranges)

Readers might enjoy Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and his Years of Pilgrimage (色彩を持たない多崎つくると、彼の巡礼の年) by Haruki Murakami. It doesn’t seem to be about autumn, but since it’s Murakami, you never really know. Anyway, it’s a great book, particularly if you are in your thirties or forties. I’d also recommend Autumn Mountain (秋山) by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, a short story about a painting (of said mountain) that possibly does or does not exist. On screen, director Yasujirō Oze’s final film An Autumn Afternoon paints an enthralling portrait of everyday life in 1960s Japan. The film's Japanese title is 秋刀魚の味 (“A Taste of Sanma”) which proves my point (see What to Eat, above) about that tasty little fish and its symbolic seasonal resonance in Japan!

Winter (冬)

箱根こす There are even some

人も有らし Who dare cross Hakone Pass

今朝の雪 Through the morning snow

Matsuo Basho (芭蕉松尾), 1644-1694

For foreign visitors, winter in Japan is most often associated with skiing and snowboarding. Frigid winds sweep down across the seas from Siberia and slam into the Japanese mountains, dropping remarkable amounts of snow, making Japan a favorite ski destination for lovers of deep soft powder. The most exciting skiing and snowboarding can be found in the Japan Alps on the main island of Honshu (where the Nagano Olympics were hosted in 1998). Hokkaido is also a favorite destination for foreign winter sports enthusiasts, with Niseko in particular being said to contain more Australians than Japanese.

Japan’s superb transportation means that access to the mountains is fantastic. It is possible (if you want) to hit the slopes in the morning and be back in Tokyo in time for apres-ski cocktails. And there are many beautiful winter views to enjoy for those who prefer a bus, a train, or their own two feet to a slippery zip down a hill (along with plenty of piping hot onsen to warm you up after!).

There is also a sharp contrast between these cold snowy mountains and the relatively mild weather you will find in the larger cities of the country tucked snugly into the flat plains along the Pacific coast. The air is cold and crisp, but snow is rare and there are many days where the sky is a quite startling deep clear blue, meaning that one can enjoy a fairly comfortable holiday in Japan's major cities even in the depths of winter.

What to Wear

If you are visiting Japan in winter, be sure to pack the following in your suitcase:

- Winter jacket

- Warm gloves

- Long underwear/base layers

- Wooly hat

- Thermal socks

- Boots/warm shoes

Many people in Japan seem to be very sensitive to cold, so you will have no problem finding thermal underwear, socks, and pajamas (finding the right size can, however, sometimes be a problem!). You can also purchase little instant warming patches popularly known as hokkairo/kairo (ホッカイロ/カイロ) to stick on under your clothing for a temporary boost of warmth.

For those accustomed to central or underfloor heating, Japanese homes can be something of a shock in winter. Heat is generally provided by spot heaters (electric or kerosene), making it more practical to heat up one room at a time than an entire building.

Hotels are generally fairly well-heated, but if you will be staying in more traditional accommodation (like a ryokan) or a friend’s home, you may want to bring warm socks and pajamas just in case the slippers and robes provided aren't quite enough.

What to Do

While skiing and snowboarding are definitely the star winter attractions for many travelers to Japan, relatively mild weather in the cities makes winter a good time to explore Japan in general if you don’t mind being a little bit chilly. There are also some stunning winter views accessible via bus, train, and cable car for those who prefer to experience winter through a window!

Skiing and snowboarding

While some foreign travelers seem to believe that ski resorts only exist on the northernmost island of Hokkaido, the most incredible skiing in Japan can actually be found on the main island of Honshu, making it easily accessible from most of Japan’s major cities.

Gala Yuzawa can be accessed via a quick shinkansen ride from Tokyo (you walk out of the station right onto the slopes), as can Karuizawa Prince Hotel Ski Resort. Those with more time can head to Hakuba, site of the 1998 Nagano Winter Olympics, which has combined 10 former ski resorts into a single massive snow sports playground!

Aside from weekends and school holidays, you will find most ski hills to be relatively empty, particularly away from the beginner slopes.

Be sure to check whether your travel health insurance covers sporting injuries incurred during skiing or snowboarding. In the (hopefully) unlikely event of an injury on the slopes, you do not want to be left with a hefty medical bill!

Onsen (hot springs)

Winter might be the best season for a soak in a pool of hot water bubbling up from under the ground! An outdoor rotenburo surrounded by snow is an unforgettable experience (you just have to survive the freezing cold walk to the tub!).

The ski resort of Zao in Yamagata prefecture is a particularly good choice if you would like to soak your aching joints after a day on the slopes. The town itself is literally steaming, with hot water running in streams throughout the town! For those looking for an especially picturesque experience, Kuroyu () in Akita (see Autumn, above) is like a winter’s dream, as is the incredible Kaniyu Onsen () in the forests north of Nikkō.

Enjoy spectacular winter views

You don’t have to strap board(s) onto your feet and jump off a cliff to enjoy the spectacular sights of winter in Japan.

Zao (see above) is also famous for the fields of “snow monsters” that flank the sides of Mount Zao. These are large trees that have been completely entombed in ice and snow due to a unique set of atmospheric conditions. A cable car (ropeway) whisks tourists overtop of these icy goliaths.

Another prime winter destination is the pristine valley of Shiragawa-go, where rare traditional A-frame gassho-zukkuri homes come to resemble gingerbread houses, their thatched roofs frosted under a thick layer of glimmering snow.

Snow sculpture enthusiasts could also check out the Sapporo Snow Festival in February.

O-shogatsu (Japanese New Year)

The New Year holiday in Japan (o-shogatsu) differs from many Western countries in that it is a family holiday (conversely, Christmas, which is not an official holiday, is often a day for going on dates!).

O-shogatsu (お正月) is a time when most businesses close down and people travel back to their hometowns to visit parents and grandparents, watch funny TV shows, and eat copious amounts of o-sechi (御節). Think turkey dinner, but with no turkey and much more cod roe.

When the clock strikes midnight, those still awake may walk to a local temple and ring the big bell. Many follow this up with a small warm bowl of soba noodles. It is then customary to make one’s first temple or shrine visit of the year, known as hatsumode, at some point in the next few days.

If you are fortunate enough to be invited to a Japanese home for o-shogatsu, it is a uniquely heartwarming (and belly-busting!) experience.

Traveling to Japan during the New Year holidays (late December, early January) can be frustrating due to packed and sold-out transportation, particularly flights and shinkansen bullet trains. Many shops and businesses are also closed at this time, especially in rural areas.

What to Eat

- Kiritanpo (long rice dumplings) - these cylindrical rice dumplings from Akita prefecture are best boiled in a nabe (stew/hotpot).

- Ramen - warm savory broth and hearty noodles are the perfect combination to chase away those winter chills.

- Kani (crab) - both Hokkaido and the Hokuriku region (Kanazawa, Fukui, etc.) are particularly renowned for their sweet, sweet kani (crab).

- Nabe (Japanese hotpot/stew) - a nabe means a large Japanese pot itself, but the word is also shorthand for a wide range of simple hotpot dishes. Essentially, it’s what you make at home in Japan in the winter when you have a bunch of ingredients, not much time, and decide that it is easiest to just throw everything into a pot. Seasonal and regional varieties abound.

- Strawberries/apples

When it comes to wintry literature, one need look no further than Yasunari Kawabata’s masterpiece Snow Country, a tragic love story between a man from the city and a geisha in a small remote winter resort. If you’d like to inject some terror into your winter, the 1968 film The Snow Woman (Yuki Onna) breathes life into the fearful yuki-onna spirit, said to appear during snowstorms, tempting men to their doom.

Summer (夏)

馬ぼくぼく Trot-trot of a horse,

我を絵に見る I find myself in a painting

夏野かな Of summer pastures

Matsuo Basho (芭蕉松尾), 1644-1694

Summer is much maligned as a season for visiting Japan, with some justification. The weather can get fairly hot, but it is the humidity that gets you, transforming even a short stroll into a steamy sweaty slog.

Still, if summer is the only time you can go, there are charms to be found in the hotter months as well.

For example, many people are unaware that Japan has many very nice beaches (it is a country composed of hundreds of islands and islets). The southern islands of Okinawa are obviously the most well-known beach destinations, but there are dozens of other spots around the country where you can enjoy sand, sun and sea.

Summer is also the time to experience some of Japan’s most impressive traditional festivals (お祭り, o-matsuri) featuring large portable shrines known as mikoshi (神輿), swirling communal dances such as bon odori (盆踊り), and all manner of tasty street food sold at yatai (temporary food stalls). Fireworks are also a long-standing fixture of the Japanese summer, frequently attended by women and men wearing attractive traditional yukatta.

If the humidity is just too much for you, consider heading north to Hokkaido. The summer there is more temperate, making it a great time for trekking, camping, or just chilling out with a barbecue next to a river or a lake.

What to Wear

If you are visiting Japan in summer, be sure to pack the following in your suitcase:

- T-shirts (breathable)

- Shorts/light trousers/skirts (quick dry)

- Hat

- Light breathable shoes, sturdy sandals

- Your favorite swimsuit

Japanese stores such as Uniqlo sell all kinds of clothing (and underclothing) specially designed for the hot summer months, in case you find yourself understocked after arrival.

If you are planning a trip to Japan in mid-June to early July, be prepared for warm weather and lots of rain. This is the tsuyu (梅雨) season, when it rains and rains…and rains. Of all times of year, this is probably the one to avoid when traveling to Japan. If you must go, an umbrella might be your best option, as you will just end up soaked with sweat if you wear a jacket. Light rain-boots are a must as well, unless you want to track muddy puddles into every building you enter.

Later in the summer (August/September), Japan is always hit by several typhoons (台風). These differ from the rainstorms of the tsuyu season in that they also bring strong winds to the country (a typhoon is essentially a Pacific hurricane). If a typhoon hits the area where you are traveling, don’t panic. Just follow the advice of local authorities (which is generally to stay indoors until the typhoon passes). Most damage in Japan from typhoons and tsuyu actually comes from mudslides caused by massive rainfall rather than high winds, so just shut the doors and windows tight, sit back, and watch the storm.

What to Do

Sand and sea take center stage in summer, with good times to be had at Japan’s many wondrous seaside parks and beaches. Crowds flock to fireworks or summer festivals (matsuri), whereas those seeking (slightly) cooler climes for camping and trekking head north to the island of Hokkaido. Whatever you do, be sure to stay hydrated, wear sunscreen, and take a break in the shade (or the air-con) from the sun (and humidity).

Go to the beach

Japan’s thousands of miles of coastline range from sheer rocky inclines to smooth sandy beaches (or piles of concrete tetrapods…).

The nation’s most popular beaches, such as those lining the Shonan Coast west of Kamakura, attract throngs of partiers, sunseekers, and surfers. Beach huts spring up for the summer to keep everyone fed and watered (all serving nice cold beer, of course).

Those in search of a more serene experience could head to Chiba prefecture (where Narita Airport is located). Nemoto Beach, at the southern tip of Chiba’s Boso peninsula, is a particularly gorgeous location, with warm sand and impressive breaking waves. Further up the east coast you will find Kujukuri Beach, a 66 km (or 99 ri, as the name implies) stretch of sand. Nothing lies between this beach and North America but the endless waves of the Pacific Ocean.

Further afield, the Izu peninsula (south of Mount Fuji) is home to many nice beaches as well as some excellent snorkeling. Shirahama Beach in Wakayama (south of Osaka) is perhaps Japan’s most surprising beach, a dazzling stretch of white sand gazing out onto some truly incredible rock formations.

Summer festivals/fireworks

Summer festivals (o-matsuri) in Japan run the gamut from humble neighborhood celebrations to huge televised spectacles with massive visual displays and teams of trained musicians and dancers. One of the charms of wandering Japan’s streets on a summer night can be happening across a local festival you never even knew was going on.

For those in search of the spectacular, it would be hard to beat Aomori’s Nebuta Matsuri, where huge illuminated floats (essentially huge-multicolored lanterns) drift through the streets and dancers welcome revelers with calls of “Rasserā!” (ラッセラー), the local version of “irasshaimase.”

Those of a more musical persuasion may prefer the Awa Odori Matsuri in Tokushima, held during O-bon, which features the twangs of the shamisen and a famous dance (the "awa-odori") performed by women clad in colorful yukatta and clamshell straw hats.

As for fireworks, you’ll find plenty of things that go bang in the night all over the country in late July and early August. All you need to do is don your yukatta, grab some cold beer or sake, and pick your spot. Tokyo’s Sumida River Fireworks is perhaps the best known, but events held at Lake Biwa (near Kyoto) and Nagaoka in Niigata prefecture both launch truly remarkable amounts of gorgeous fiery ordnance into the night sky.

Be sure to book accommodation and transportation well in advance if you plan to take in one of Japan's most popular summer matsuri events. Hotels typically sell out months in advance.

Trekking and Camping in Hokkaido

Hokkaido is the one part of Japan that experiences mild temperatures and humidity in summer, making it a great destination for fans of the outdoors. The island’s many national parks with their picturesque rivers and lakes make it an ideal destination for camping and trekking, or just chilling out with a barbecue and a beverage.

Campers could choose to pitch their tent near Lake Toya in the southern part of the island or gaze up at the stars from Hoshinite-no-todoku-oka campground near Furano. Trekkers could head to the tiny island of Rishiri at the northern end of Hokkaido to climb its mountain and gaze across the sea to Russia. The truly adventurous can venture out into the remote wilderness of the Shiretoko peninsula.

What to Eat

- Hiyashi-chuka - sliced tomato, shredded omelet, pork chashu strips, thin-sliced cucumber, and other delicious summery toppings, all atop a bed of chilled ramen noodles.

- So-men noodles - delicate little wheat noodles, usually served cold in a light soy sauce-based broth.

- Grilled unagi (eel) - strips of grilled eel served on a bed of white rice with pickles is a perfect treat any time of year, but somehow tastes best in summer.

- Suica (watermelon), nashi (Japanese “apple-pears”)

- Kaki-gori (shaved ice) - Japan’s favorite summer treat, conventionally composed of syrup-flavored ice shavings, is now available at fancy shops with toppings ranging from fresh fruit to candy to adzuki beans.

Yukio Mishima’s The Sound of Waves, set on a tiny (and sadly fictional) island, is a beautifully written chronicle of young love. It features one descriptive passage of ama-san (traditional female divers in Japan who collect shellfish from the ocean floor) at work that is among the finest pieces of prose in Japanese literature. On your screen, re-watching the films of Studio Ghibli is something of a national summer pastime, with My Neighbour Totoro perhaps the pick of them all in terms of childhood nostalgia.

Conclusion: When is the best time of year to visit Japan?

Spring and autumn are without question the most comfortable times of year to visit Japan, but this also makes them the most popular. Whether or not you are willing to brave the crowds to enjoy the pink blossoms of spring or the red leaves of autumn is very much a matter of personal preference. Shifting your trip away from peak times may make the whole experience more enjoyable.

Winter is also an excellent time to visit Japan due to the country’s abundant opportunities for winter sports such as skiing and snowboarding. Temperatures in major cities are also fairly mild, making winter a decent alternative option for visiting cultural sites.

Summer is hot and humid, making travel sweaty work, but its spectacular festivals (o-matsuri) and fireworks displays can make it all worthwhile. And you can always head to the beach (or Hokkaido) to try to cool off! The rainy season (tsuyu, 梅雨) of late June/early July is best avoided if possible.

Overall though, the best advice is maybe not to overplan. You want great memories, and great photos, but they don’t need to look like everyone else’s. Take the seasons into consideration, but remember that really there is no bad time to take a trip to the Land of the Rising Sun.

The best time to travel to Japan is as soon as you can!